Should you trust your money to hedge funds?

In 2008, billionaire Warren Buffett wagered $ 1 million with hedge fund managers (actively-managed funds with high commissions).

He bet that a passively managed US stock market index fund (S&P 500) will overtake actively managed hedge funds in 10 years.

That is, an investor who “knows nothing” and “does nothing” will outplay the professionals. The results were surprising.

In a letter to the shareholders shareholders of his fund, he described the famous rate as follows:

(Buffett's text, and some of the subheadings are mine for ease of reading)

THE BET (OR HOW YOUR MONEY FINDS ITS WAY TO WALL STREET)

In this section, you will encounter, early on, the story of an investment bet I made nine years ago and, next, some strong opinions I have about investing. As a starter, though, I want to briefly describe Long Bets, a unique establishment that played a role in the bet.

Long Bets was seeded by Amazon’s Jeff Bezos and operates as a non-profit organization that administers just what you’d guess: long-term bets. To participate, “proposers” post a proposition at Longbets.org that will be proved right or wrong at a distant date. They then wait for a contrary-minded party to take the other side of the bet. When a “doubter” steps forward, each side names a charity that will be the beneficiary if its side wins; parks its wager with Long Bets; and posts a short essay defending its position on the Long Bets website. When the bet is concluded, Long Bets pays off the winning charity.

Here are examples of what you will find on Long Bets’ very interesting site: In 2002, entrepreneur Mitch Kapor asserted that “By 2029 no computer – or ‘machine intelligence’ – will have passed the Turing Test,” which deals with whether a computer can successfully impersonate a human being. Inventor Ray Kurzweil took the opposing view. Each backed up his opinion with $10,000. I don’t know who will win this bet, but I will confidently wager that no computer will ever replicate Charlie.

That same year, Craig Mundie of Microsoft asserted that pilotless planes would routinely fly passengers by 2030, while Eric Schmidt of Google argued otherwise. The stakes were $1,000 each. To ease any heartburn Eric might be experiencing from his outsized exposure, I recently offered to take a piece of his action. He promptly laid off $500 with me. (I like his assumption that I’ll be around in 2030 to contribute my payment, should we lose.)

DISPUTE HISTORY

Now, to my bet and its history. In Berkshire’s 2005 annual report, I argued that active investment management by professionals – in aggregate – would over a period of years underperform the returns achieved by rank amateurs who simply sat still. I explained that the massive fees levied by a variety of “helpers” would leave their clients – again in aggregate – worse off than if the amateurs simply invested in an unmanaged low-cost index fund. (See pages 114 - 115 for a reprint of the argument as I originally stated it in the 2005 report.)

Subsequently, I publicly offered to wager $500,000 that no investment pro could select a set of at least five hedge funds – wildly-popular and high-fee investing vehicles – that would over an extended period match the performance of an unmanaged S&P-500 index fund charging only token fees. I suggested a ten-year bet and named a low-cost Vanguard S&P fund as my contender. I then sat back and waited expectantly for a parade of fund managers – who could include their own fund as one of the five – to come forth and defend their occupation. After all, these managers urged others to bet billions on their abilities. Why should they fear putting a little of their own money on the line?

What followed was the sound of silence.

CHALLENGE ACCEPTED

Though there are thousands of professional investment managers who have amassed staggering fortunes by touting their stock-selecting prowess, only one man – Ted Seides – stepped up to my challenge. Ted was a co-manager of Protégé Partners, an asset manager that had raised money from limited partners to form a fund-of-funds – in other words, a fund that invests in multiple hedge funds.

I hadn’t known Ted before our wager, but I like him and admire his willingness to put his money where his mouth was. He has been both straight-forward with me and meticulous in supplying all the data that both he and I have needed to monitor the bet.

For Protégé Partners’ side of our ten-year bet, Ted picked five funds-of-funds whose results were to be averaged and compared against my Vanguard S&P index fund. The five he selected had invested their money in more than 100 hedge funds, which meant that the overall performance of the funds-of-funds would not be distorted by the good or poor results of a single manager.

Each fund-of-funds, of course, operated with a layer of fees that sat above the fees charged by the hedge funds in which it had invested. In this doubling-up arrangement, the larger fees were levied by the underlying hedge funds; each of the fund-of-funds imposed an additional fee for its presumed skills in selecting hedge-fund managers.

PRELIMINARY RESULTS

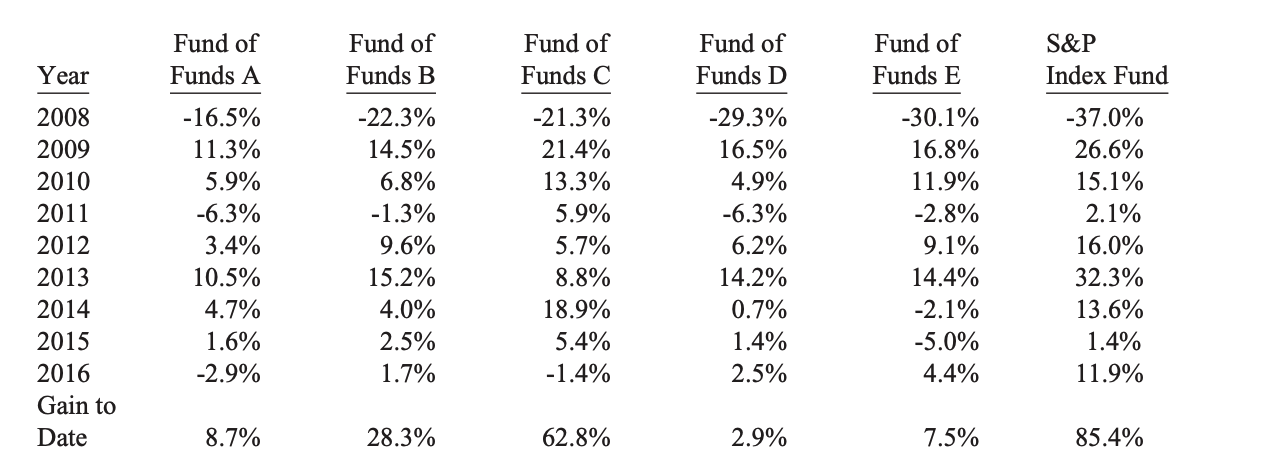

Here are the results for the first nine years of the bet – figures leaving no doubt that Girls Inc. of Omaha, the charitable beneficiary I designated to get any bet winnings I earned, will be the organization eagerly opening the mail next January.

Under my agreement with Protégé Partners, the names of these funds-of-funds have never been publicly disclosed. I, however, see their annual audits.

The compounded annual increase to date for the index fund is 7.1%, which is a return that could easily prove typical for the stock market over time. That’s an important fact: A particularly weak nine years for the market over the lifetime of this bet would have probably helped the relative performance of the hedge funds, because many hold large “short” positions. Conversely, nine years of exceptionally high returns from stocks would have provided a tailwind for index funds.

Instead we operated in what I would call a “neutral” environment. In it, the five funds-of-funds delivered, through 2016, an average of only 2.2%, compounded annually. That means $1 million invested in those funds would have gained $220,000. The index fund would meanwhile have gained $854,000.

Bear in mind that every one of the 100-plus managers of the underlying hedge funds had a huge financial incentive to do his or her best. Moreover, the five funds-of-funds managers that Ted selected were similarly incentivized to select the best hedge-fund managers possible because the five were entitled to performance fees based on the results of the underlying funds.

I’m certain that in almost all cases the managers at both levels were honest and intelligent people. But the results for their investors were dismal – really dismal.

WHY MANAGERS LOST

And, alas, the huge fixed fees charged by all of the funds and funds-of-funds involved – fees that were totally unwarranted by performance – were such that their managers were showered with compensation over the nine years that have passed. As Gordon Gekko might have put it: “Fees never sleep.”

The underlying hedge-fund managers in our bet received payments from their limited partners that likely averaged a bit under the prevailing hedge-fund standard of “2 and 20,” meaning a 2% annual fixed fee, payable even when losses are huge, and 20% of profits with no clawback (if good years were followed by bad ones). Under this lopsided arrangement, a hedge fund operator’s ability to simply pile up assets under management has made many of these managers extraordinarily rich, even as their investments have performed poorly.

Still, we’re not through with fees. Remember, there were the fund-of-funds managers to be fed as well. These managers received an additional fixed amount that was usually set at 1% of assets. Then, despite the terrible overall record of the five funds-of-funds, some experienced a few good years and collected “performance” fees. Consequently, I estimate that over the nine-year period roughly 60% – gulp! – of all gains achieved by the five funds-of-funds were diverted to the two levels of managers. That was their misbegotten reward for accomplishing something far short of what their many hundreds of limited partners could have effortlessly – and with virtually no cost – achieved on their own.

In my opinion, the disappointing results for hedge-fund investors that this bet exposed are almost certain to recur in the future.

MY ARGUMENTS

I laid out my reasons for that belief in a statement that was posted on the Long Bets website when the bet commenced (and that is still posted there). Here is what I asserted:

- Over a ten-year period commencing on January 1, 2008, and ending on December 31, 2017, the S&P 500 will outperform a portfolio of funds of hedge funds, when performance is measured on a basis net of fees, costs and expenses.

- A lot of very smart people set out to do better than average in securities markets. Call them active investors.

- Their opposites, passive investors, will by definition do about average. In aggregate their positions will more or less approximate those of an index fund. Therefore, the balance of the universe—the active investors—must do about average as well. However, these investors will incur far greater costs. So, on balance, their aggregate results after these costs will be worse than those of the passive investors.

- Costs skyrocket when large annual fees, large performance fees, and active trading costs are all added to the active investor’s equation. Funds of hedge funds accentuate this cost problem because their fees are superimposed on the large fees charged by the hedge funds in which the funds of funds are invested.

- A number of smart people are involved in running hedge funds. But to a great extent their efforts are self-neutralizing, and their IQ will not overcome the costs they impose on investors. Investors, on average and over time, will do better with a low-cost index fund than with a group of funds of funds.

So that was my argument – and now let me put it into a simple equation. If Group A (active investors) and Group B (do-nothing investors) comprise the total investing universe, and B is destined to achieve average results before costs, so, too, must A. Whichever group has the lower costs will win. (The academic in me requires me to mention that there is a very minor point – not worth detailing – that slightly modifies this formulation.) And if Group A has exorbitant costs, its shortfall will be substantial.

There are, of course, some skilled individuals who are highly likely to out-perform the S&P over long stretches. In my lifetime, though, I’ve identified – early on – only ten or so professionals that I expected would accomplish this feat.

There are no doubt many hundreds of people – perhaps thousands – whom I have never met and whose abilities would equal those of the people I’ve identified. The job, after all, is not impossible. The problem simply is that the great majority of managers who attempt to over-perform will fail. The probability is also very high that the person soliciting your funds will not be the exception who does well. Bill Ruane – a truly wonderful human being and a man whom I identified 60 years ago as almost certain to deliver superior investment returns over the long haul – said it well: “In investment management, the progression is from the innovators to the imitators to the swarming incompetents.”

Further complicating the search for the rare high-fee manager who is worth his or her pay is the fact that some investment professionals, just as some amateurs, will be lucky over short periods. If 1,000 managers make a market prediction at the beginning of a year, it’s very likely that the calls of at least one will be correct for nine consecutive years. Of course, 1,000 monkeys would be just as likely to produce a seemingly all-wise prophet. But there would remain a difference: The lucky monkey would not find people standing in line to invest with him.

Finally, there are three connected realities that cause investing success to breed failure. First, a good record quickly attracts a torrent of money. Second, huge sums invariably act as an anchor on investment performance: What is easy with millions, struggles with billions (sob!). Third, most managers will nevertheless seek new money because of their personal equation – namely, the more funds they have under management, the more their fees.

These three points are hardly new ground for me: In January 1966, when I was managing $44 million, I wrote my limited partners: “I feel substantially greater size is more likely to harm future results than to help them. This might not be true for my own personal results, but it is likely to be true for your results. Therefore, . . . I intend to admit no additional partners to BPL. I have notified Susie that if we have any more children, it is up to her to find some other partnership for them.”

The bottom line: When trillions of dollars are managed by Wall Streeters charging high fees, it will usually be the managers who reap outsized profits, not the clients. Both large and small investors should stick with low-cost index funds.

In February 2018, in a letter to shareholders, Buffett summarized his dispute:

“THE BET” IS OVER AND HAS DELIVERED AN UNFORESEEN INVESTMENT LESSON

Last year, at the 90% mark, I gave you a detailed report on a ten-year bet I had made on December 19, 2007. (The full discussion from last year’s annual report is reprinted on pages 24 – 26.) Now I have the final tally – and, in several respects, it’s an eye-opener.

I made the bet for two reasons: (1) to leverage my outlay of $318,250 into a disproportionately larger sum that – if things turned out as I expected – would be distributed in early 2018 to Girls Inc. of Omaha; and (2) to publicize my conviction that my pick – a virtually cost-free investment in an unmanaged S&P 500 index fund – would, over time, deliver better results than those achieved by most investment professionals, however well-regarded and incentivized those “helpers” may be.

Addressing this question is of enormous importance. American investors pay staggering sums annually to advisors, often incurring several layers of consequential costs. In the aggregate, do these investors get their money’s worth? Indeed, again in the aggregate, do investors get anything for their outlays?

Protégé Partners, my counterparty to the bet, picked five “funds-of-funds” that it expected to overperform the S&P 500. That was not a small sample. Those five funds-of-funds in turn owned interests in more than 200 hedge funds.

Essentially, Protégé, an advisory firm that knew its way around Wall Street, selected five investment experts who, in turn, employed several hundred other investment experts, each managing his or her own hedge fund. This assemblage was an elite crew, loaded with brains, adrenaline and confidence.

The managers of the five funds-of-funds possessed a further advantage: They could – and did – rearrange their portfolios of hedge funds during the ten years, investing with new “stars” while exiting their positions in hedge funds whose managers had lost their touch.

Every actor on Protégé’s side was highly incentivized: Both the fund-of-funds managers and the hedge-fund managers they selected significantly shared in gains, even those achieved simply because the market generally moves upwards. (In 100% of the 43 ten-year periods since we took control of Berkshire, years with gains by the S&P 500 exceeded loss years.)

Those performance incentives, it should be emphasized, were frosting on a huge and tasty cake: Even if the funds lost money for their investors during the decade, their managers could grow very rich. That would occur because fixed fees averaging a staggering 21⁄2% of assets or so were paid every year by the fund-of-funds’ investors, with part of these fees going to the managers at the five funds-of-funds and the balance going to the 200-plus managers of the underlying hedge funds.

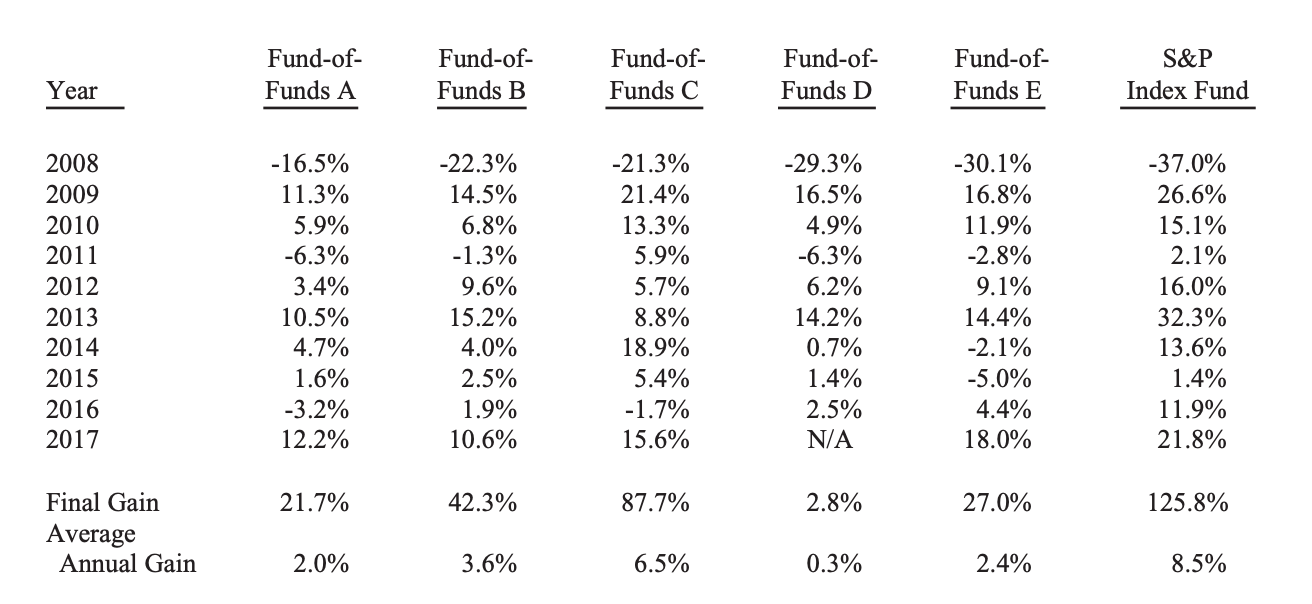

Here’s the final scorecard for the bet:

Under my agreement with Protégé Partners, the names of these funds-of-funds have never been publicly disclosed. I, however, have received their annual audits from Protégé. The 2016 figures for funds A, B and C were revised slightly from those originally reported last year. Fund D was liquidated in 2017; its average annual gain is calculated for the nine years of its operation.

The five funds-of-funds got off to a fast start, each beating the index fund in 2008. Then the roof fell in. In every one of the nine years that followed, the funds-of-funds as a whole trailed the index fund.

Let me emphasize that there was nothing aberrational about stock-market behavior over the ten-year stretch. If a poll of investment “experts” had been asked late in 2007 for a forecast of long-term common-stock returns, their guesses would have likely averaged close to the 8.5% actually delivered by the S&P 500. Making money in that environment should have been easy. Indeed, Wall Street “helpers” earned staggering sums. While this group prospered, however, many of their investors experienced a lost decade.

Performance comes, performance goes. Fees never falter

ONE MORE LESSON

The bet illuminated another important investment lesson: Though markets are generally rational, they occasionally do crazy things. Seizing the opportunities then offered does not require great intelligence, a degree in economics or a familiarity with Wall Street jargon such as alpha and beta. What investors then need instead is an ability to both disregard mob fears or enthusiasms and to focus on a few simple fundamentals. A willingness to look unimaginative for a sustained period – or even to look foolish – is also essential.

Originally, Protégé and I each funded our portion of the ultimate $1 million prize by purchasing $500,000 face amount of zero-coupon U.S. Treasury bonds (sometimes called “strips”). These bonds cost each of us $318,250 – a bit less than 64¢ on the dollar – with the $500,000 payable in ten years.

As the name implies, the bonds we acquired paid no interest, but (because of the discount at which they were purchased) delivered a 4.56% annual return if held to maturity. Protégé and I originally intended to do no more than tally the annual returns and distribute $1 million to the winning charity when the bonds matured late in 2017.

After our purchase, however, some very strange things took place in the bond market. By November 2012, our bonds – now with about five years to go before they matured – were selling for 95.7% of their face value. At that price, their annual yield to maturity was less than 1%. Or, to be precise, 0.88%.

Given that pathetic return, our bonds had become a dumb – a really dumb – investment compared to American equities. Over time, the S&P 500 – which mirrors a huge cross-section of American business, appropriately weighted by market value – has earned far more than 10% annually on shareholders’ equity (net worth).

In November 2012, as we were considering all this, the cash return from dividends on the S&P 500 was 21⁄2% annually, about triple the yield on our U.S. Treasury bond. These dividend payments were almost certain to grow. Beyond that, huge sums were being retained by the companies comprising the 500. These businesses would use their retained earnings to expand their operations and, frequently, to repurchase their shares as well. Either course would, over time, substantially increase earnings-per-share. And – as has been the case since 1776 – whatever its problems of the minute, the American economy was going to move forward.

Presented late in 2012 with the extraordinary valuation mismatch between bonds and equities, Protégé and I agreed to sell the bonds we had bought five years earlier and use the proceeds to buy 11,200 Berkshire “B” shares. The result: Girls Inc. of Omaha found itself receiving $2,222,279 last month rather than the $1 million it had originally hoped for.

Berkshire, it should be emphasized, has not performed brilliantly since the 2012 substitution. But brilliance wasn’t needed: After all, Berkshire’s gain only had to beat that annual .88% bond bogey – hardly a Herculean achievement.

The only risk in the bonds-to-Berkshire switch was that yearend 2017 would coincide with an exceptionally weak stock market. Protégé and I felt this possibility (which always exists) was very low. Two factors dictated this conclusion: The reasonable price of Berkshire in late 2012, and the large asset build-up that was almost certain to occur at Berkshire during the five years that remained before the bet would be settled. Even so, to eliminate all risk to the charities from the switch, I agreed to make up any shortfall if sales of the 11,200 Berkshire shares at yearend 2017 didn’t produce at least $1 million.

Investing is an activity in which consumption today is foregone in an attempt to allow greater consumption at a later date. “Risk” is the possibility that this objective won’t be attained.

By that standard, purportedly “risk-free” long-term bonds in 2012 were a far riskier investment than a longterm investment in common stocks. At that time, even a 1% annual rate of inflation between 2012 and 2017 would have decreased the purchasing-power of the government bond that Protégé and I sold.

I want to quickly acknowledge that in any upcoming day, week or even year, stocks will be riskier – far riskier – than short-term U.S. bonds. As an investor’s investment horizon lengthens, however, a diversified portfolio of U.S. equities becomes progressively less risky than bonds, assuming that the stocks are purchased at a sensible multiple of earnings relative to then-prevailing interest rates.

It is a terrible mistake for investors with long-term horizons – among them, pension funds, college endowments and savings-minded individuals – to measure their investment “risk” by their portfolio’s ratio of bonds to stocks. Often, high-grade bonds in an investment portfolio increase its risk.

THE FINAL LESSON FROM OUR BET

A final lesson from our bet: Stick with big, “easy” decisions and eschew activity. During the ten-year bet, the 200-plus hedge-fund managers that were involved almost certainly made tens of thousands of buy and sell decisions. Most of those managers undoubtedly thought hard about their decisions, each of which they believed would prove advantageous. In the process of investing, they studied 10-Ks, interviewed managements, read trade journals and conferred with Wall Street analysts.

Protégé and I, meanwhile, leaning neither on research, insights nor brilliance, made only one investment decision during the ten years. We simply decided to sell our bond investment at a price of more than 100 times earnings (95.7 sale price/.88 yield), those being “earnings” that could not increase during the ensuing five years.

We made the sale in order to move our money into a single security – Berkshire – that, in turn, owned a diversified group of solid businesses. Fueled by retained earnings, Berkshire’s growth in value was unlikely to be less than 8% annually, even if we were to experience a so-so economy.

After that kindergarten-like analysis, Protégé and I made the switch and relaxed, confident that, over time, 8% was certain to beat 0.88%. By a lot.

This concludes the quotation from Buffett's letters. You might be wondering what the losers answered.

LOSERS ANSWER

As a result of the bet, the loser, Ted Sides, announced that Buffett's win was not only related to the high management fees. He pointed out that the S&P 500 is targeting large US companies that have shown gains in recent years.

Hedge funds, on the other hand, are more focused on international companies - and indices that include similar companies have shown growth similar to that of hedge funds. He also noted that in a declining market, hedge fund investors tend to earn more than index fund investors.

Other hedge fund employees wrote that Ted chose overly conservative funds, which find it difficult to outrun the stock index over a 10-year period.

All of this may be true, but the following is obvious: it is not so easy to choose funds that, after deducting all fees, will overtake the stock index.

Competition among active funds is a zero-sum game. Winning funds win at the expense of losers and the sum is the average.

Further, if you subtract commissions from the profits of active funds, it turns out that, on average, the results of hedge funds are below average, and a passive investor is more successful than an active one.

Based on this, it is understandable why Buffett recommends passive investments to his friends.